Extremadura is one of those places you want everyone to know about, but also want to have entirely to yourself.

Nestled between Madrid and Andalusia, it’s an oft-overlooked part of Spain and not easy to explore without a car. Rich in history, the western plains of Spain were home to the largest and most powerful Roman cities in Hispania, as well as the birthplace of the conquistadores who conquered much of Latin and South America. This legacy has been left in the jewels littered throughout the comunidad autónoma in Guadalupe’s sprawling monastery, the monument-rich Cáceres and Roman Mérida.

In many ways, spending time in Extremadura can make you feel like time has stopped, but even Spaniards look at it with disdain, citing poor transportation links and a lack of things to do. Just like Americans can’t place Iowa on a map, Extemadura to many Spaniards is a corner of Spain that serves as a gateway to Portugal and Andalucía, and little else.

Suckers.

When a free weekend came up in July, I called up two friends in Sevilla and one in Madrid, and we met in the middle. The town of Trujillo is equidistant between the capital of Spain and the capital of Andalusia, and an easy jaunt on the A-5 highway that connects the southwest of Spain and central Portugal to Madrid.

Follow the trail of the Conquistadores

Name any conqueror from the 16th Century. Save a select few, the big names all came from Extremadura – Pizarro, Núñez de Balboa, Hernán Cortés. Loyal to the Spanish crown, they claimed a sizeable chunks of land, changing the course of history and effectively bringing the Spanish language, culture and communicable diseases to the New World.

Ever drawn the conclusion that of South America’s great cities are named for Spanish towns? Most of those pueblos, like Medellín or even Trujillo, are extremeño towns. On my first trip to Extremadura, a lifelong extremeña told me that the name of her comunidad autónoma came from these mean from the far-lying (extre) provinces whose lives were hardened on the western plains (madura). Take it for what you will, but extremeños have since been known for their gumption.

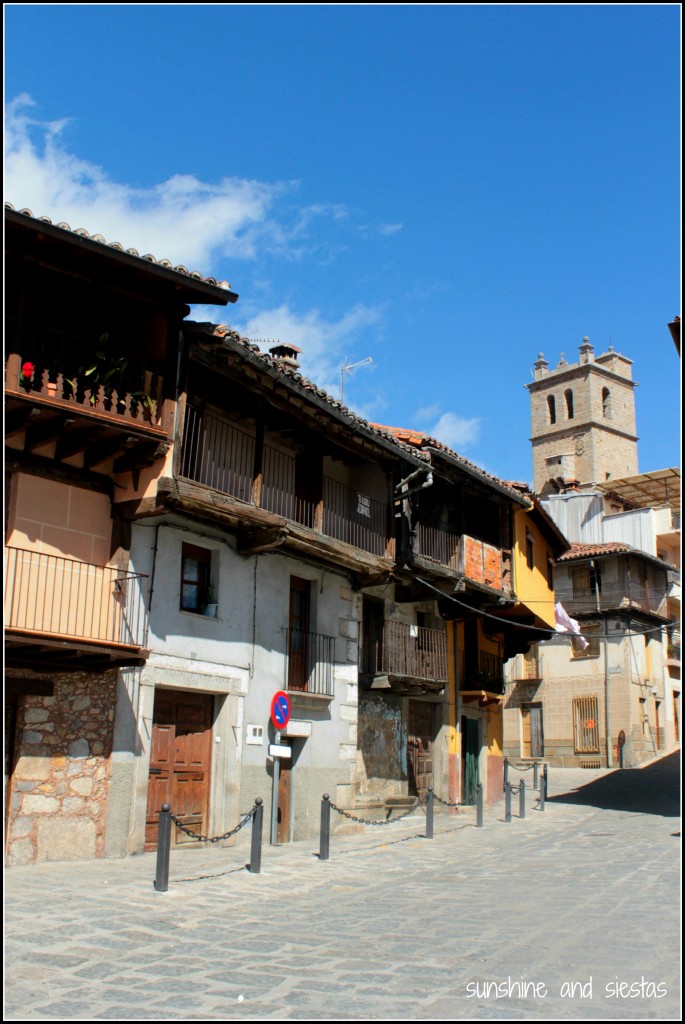

The cornerstone of an already gorgeous main square, the Plaza Mayor de Trujillo, the Palacio de la Conquista’s erection was financed largely in part by the riches Pizarro brought back from Peru. It sits at the bottom of a hill that is crowned by a crumbling alcazaba, and the stone mansions and plazas that tumble down are of note.

It’s honestly one of the most beautiful villages I’ve been to in Spain, and I’ve been to a lot.

Many of the palaces have since been converted into hotels and restaurants, but a morning walk will allow you to see the highlights. Aside from whether or not they pillaged or brought disease, the architectural legacy is staggering. Oh, and Pizarro reputedly brought over a Spanish food staple – tomatoes.

If you want to go further afield and have a car, Trujillo is about equidistant to Cáceres and Mérida, the administrative capital of Extremadura. The Tourism Board suggests the Ruta de los Descubridores, which traces from Plasencia to Trujillo before heading west to Cáceres. Continuing south, you’ll get to Villanueva de la Serena, Medellīn and Mérida; the outpost of Badajóz is a bit further out but is the last stop.

Day trips to Guadalupe and Yuste / the Jerte Valley

My first go at Trujillo was at the hand of a contest won by Trujillo Villas. We had a long weekend, a car and plenty of time to kill on our way up the A-66. Turning off at Valdivia, a small suburb of Villanueva de la Serena (surprise! home to conquistador Pedro de Valdivia), the road snakes into the foothills towards the town of Guadalupe and the Monasterio de Santa María de Guadalupe.

According to legend, the veneration may have been carved in the 1st Century by Saint Luke himself, who then carted her around the world before presenting the Archbishop of Seville, San Leandro, with it. During the Moorish invasion that commenced in 711, the Archdiocese of Seville looked for a place to hide her as invaders ransacked cities and palaces.

Like all great pilgrimage sites, like the ending points of the Camino de Santiago or El Rocío, Guadalupe has attracted illustrious names in Spanish history – Columbus prayed here after returning from the New World (and the Madonna is now revered in Central and South America), King Alfonso XI invoked Guadalupe’s spirit during the Battle of Salado, and many modern-day popes have stopped to worship. It’s even one of Spain’s UNESCO World Heritage Sites and is well-deserving of the nod. Seriously. Do not miss this one.

Further north and part of the Sierra de Gredos lie a number of small hamlets that look like they belong in Shakespeare’s novels than rural Spain. The Gargantas, or a series of natural pools in the foothills, and its largest town, Garganta la Olla, is worth a few hours’ walk to stretch your legs and lunch.

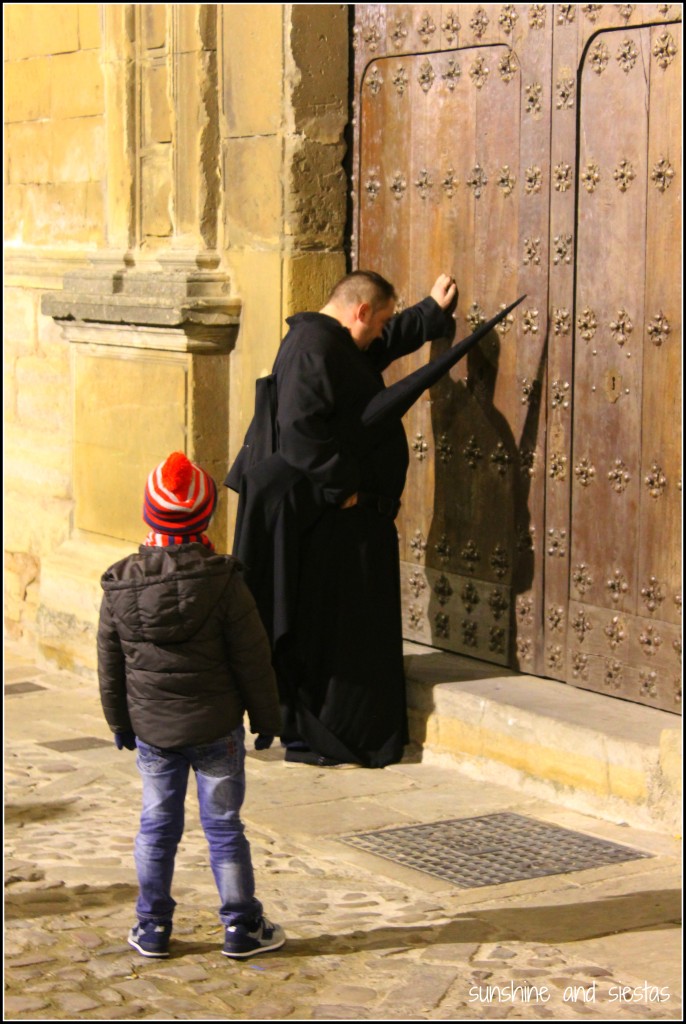

Just 10 minutes northeast of Garganta la Olla is the Monastery of San Jerónimo de Yuste, one of Spain’s patrimonial highlights and where Holy Roman Emporer Charles V retired to live out his days. Formerly inhabited by Hieronymite and boasting picturesque views of the almond tree-covered countryside it’s no wonder he made the treacherous trip from Madrid to Yuste (and El Escorial wouldn’t be ordered to be built for another five years anyway).

While it was a disappointment to us with pushy tour guides and a steep price tag, the drive through almond trees in bloom and waterfalls was worth the extra kilometers.

Other towns you might want to explore are Zafra, south of Mérida, and Jerez de los Caballeros. Or, really any town with a castle.

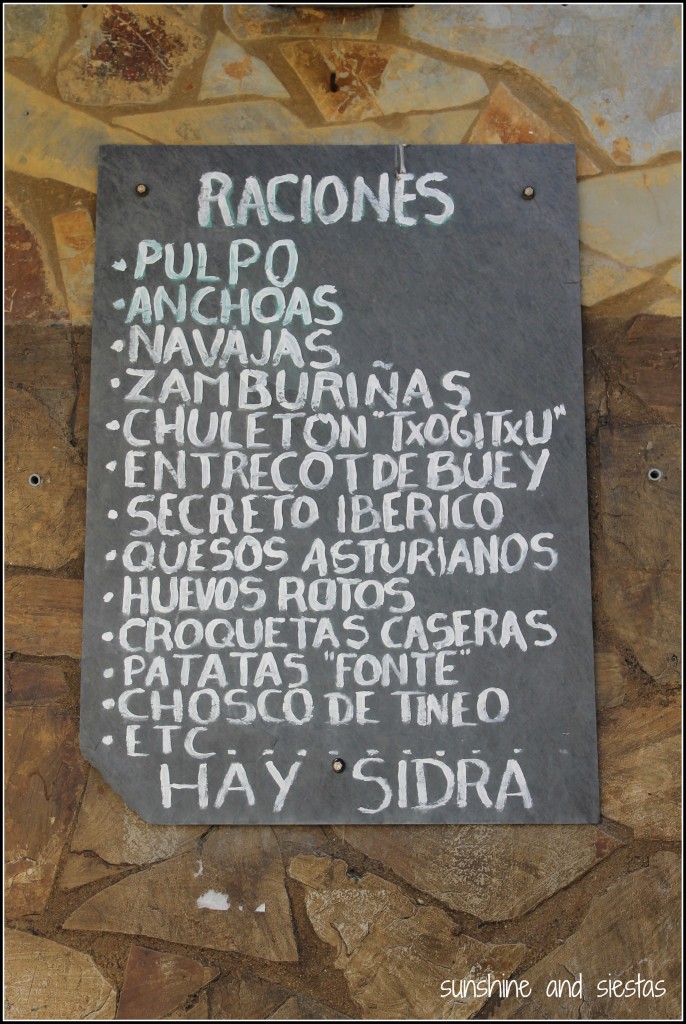

Eat

Extremadura prides itself on its food – from hearty game and foul and some of the best jamón ibérico de bellota to Torta del Casar, the notoriously stinky cheese (believe me when I saw it smells like feet). Famous for its sweet, smoked paprika and hearty, little-consumed wines. For its sweets and earthy breads. Characterized by its simplicity and complexity (like all great Spanish dishes), you can eat on the cheap just about anywhere in the region.

In a small city like Trujillo, there are few options. I had been to famed Casa Troya, a locale famous for its location on the Plaza Mayor and its patronage, on a previous visit and was not ready to return. The first night, restless but tired after our early wake up calls for work and the drive, we settled on Hermanos Marcelo in the square for their croquetas and plenty of helpings of embutidos, or cured meats.

On Saturday morning, we were able to sneak on a last-minute tour of Bodegas Habla, located just to the south of the village.

In operation from 1999, Bodegas Habla is one of the newest and most innovative wineries in all of Spain – and it produces a table wine that can be drunk as if it was a special occasion. I don’t pretend to know anything about wine other than that it’s made from grapes and I like it less than beer, but I bought into the energy, the marketing and the experience of Habla.

The tour and tasting cost 13€, which included four wines – their signature Habla del Silencio, Rita, Habla de tí and a limited edition 13. You can contact the Bodega at habla@bodegashabla.com for more information and availability.

While there is parking on-site, please consider finding a designated driver or calling a local taxi. We opted for the latter and, true to his word, he came back in two hours for us and dropped us right off at the restaurant La Alberca.

Perhaps Trujillo’s biggest draw is their Feria del Queso de Trujillo, an artisan fair dedicated solely to cheese. Held around May 1st each year, around 200,000 people are drawn to the Plaza Mayor for activities and tastings centered around goat and sheep cheeses. Area restaurants create special menus in which local cheeses are the main feature. Considering how much I love cheese, I’m shocked I haven’t made it there yet.

Where to eat in Trujillo?

If you’re spending any time in Trujillo, skip Casa Troya and make sure to make a reservation at La Alberca (C/Cambrones, 8). Between the stone walls and the breezy patio, plus a selection of wines from the region – D.O. Tierra de Barro is a great choice if you’re feeling adventurous or want something hearty – this place delivered on food, service and experience. We got away with about 18€ a head.

The Takeaway

I first saw Trujillo driving up to Valladolid with the Novio after about four months living in Seville. The fortress seemed to appear out of nowhere in the middle of the plains, and I pressed my nose to the window to see it from all angles. It may be small, but it packs that distinctly Spanish punch: the wine, the food and the cultural legacy make it worthy of stopping for a night or if you’re en route to Cáceres. In fact, put Extremadura in general on your list.

Have you been to Trujillo and Extremadura? Anything I missed on this list?

Here’s a little plug for our super cute AirBnB with two terraces and gorgeous views down to the Plaza Mayor. We seriously loved this place so much that we decided to not even go out but just drink wine and play boardgames! It’s a gem and you can park nearby.