Not one to make travel goals, I did make one when coming to Spain: visit all 17 autonomous communities at least once before going home. While Madrid, Barcelona and Seville are the stars of the tourist dollar show (and my hard-earned euros, let’s not kid around here), I am a champion for Spain’s little-known towns and regions. Having a global view of this country has come through living in Andalucía, working in Galicia and studying in Castilla y León, plus extensive travel throughout Spain.

I was fascinated with the Basque Country from my time studying abroad. Our shared bedroom was sparse, but had a detailed map of Spain plastered onto the wall, and I’d usually stare it before taking my siesta. Just north of Castilla y León lay a land where Zs and Xs and Ks seemed to make up all of the towns and cities, and once I began modern culture classes at the Universidad de Valladolid, I realized how different Spain was from region to region.

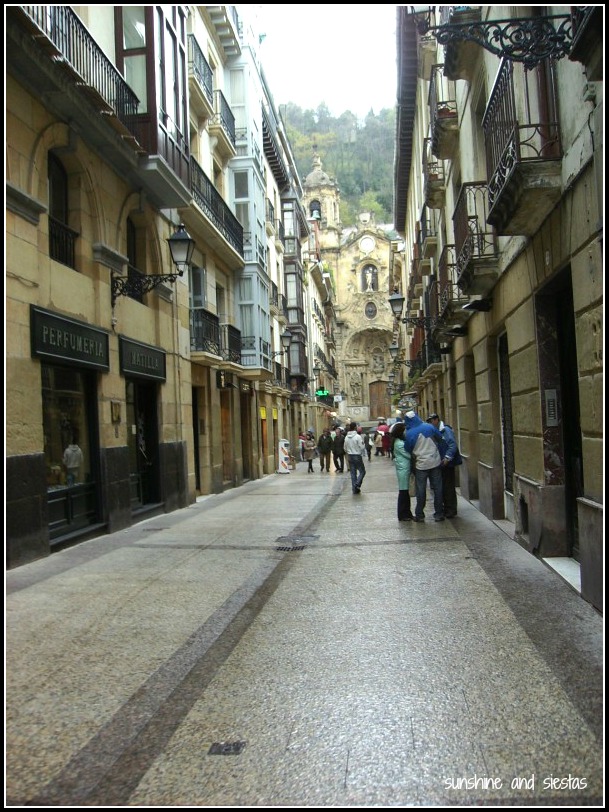

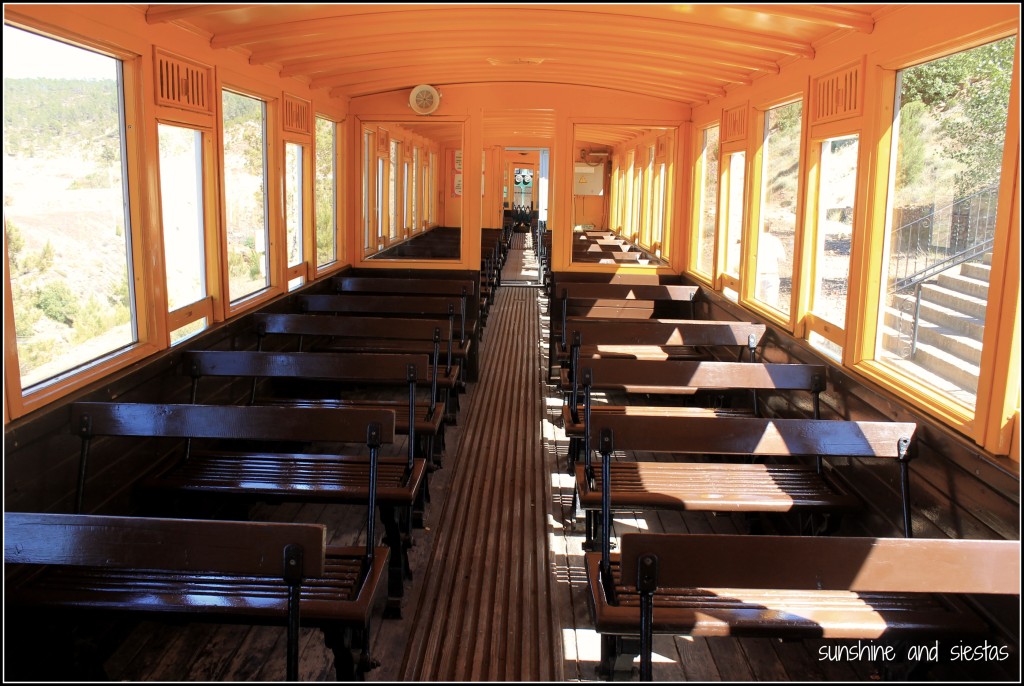

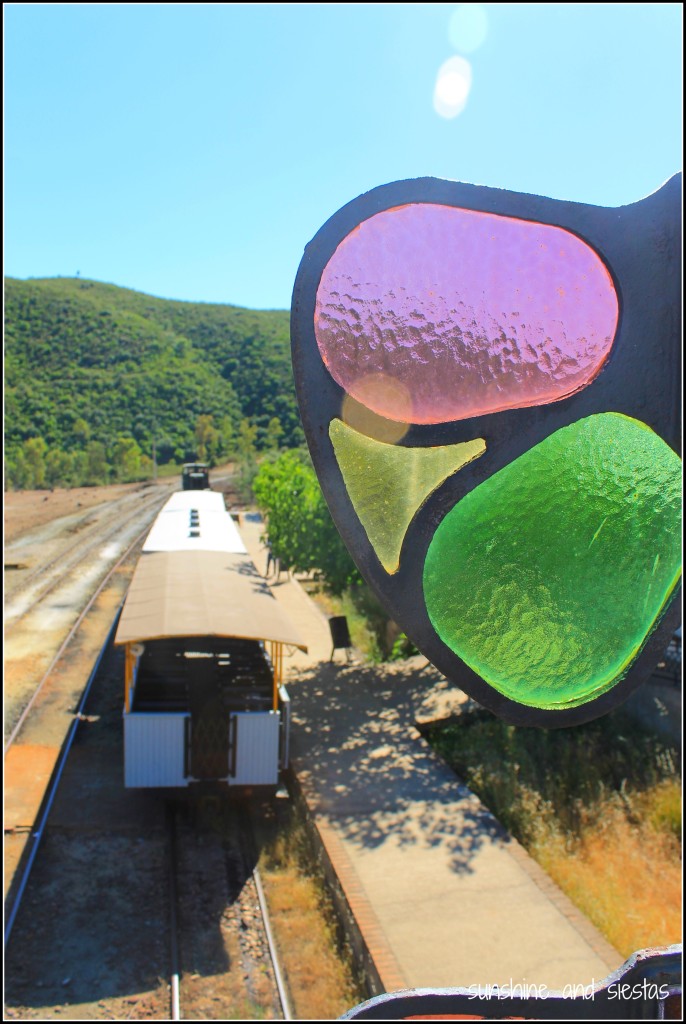

I jumped at the chance to visit regal San Sebastián and hip Bilbao during a long weekend, traveling five hours north by train. The arid meseta – experiencing a drought that summer – gave way to the lush gardens of Vitoria and rolling hills. I noticed the roofs slanted because of the rain. The words on shops and billboards became illegible. Tapas were served on bread.

Toto, we’re not in Spain anymore.

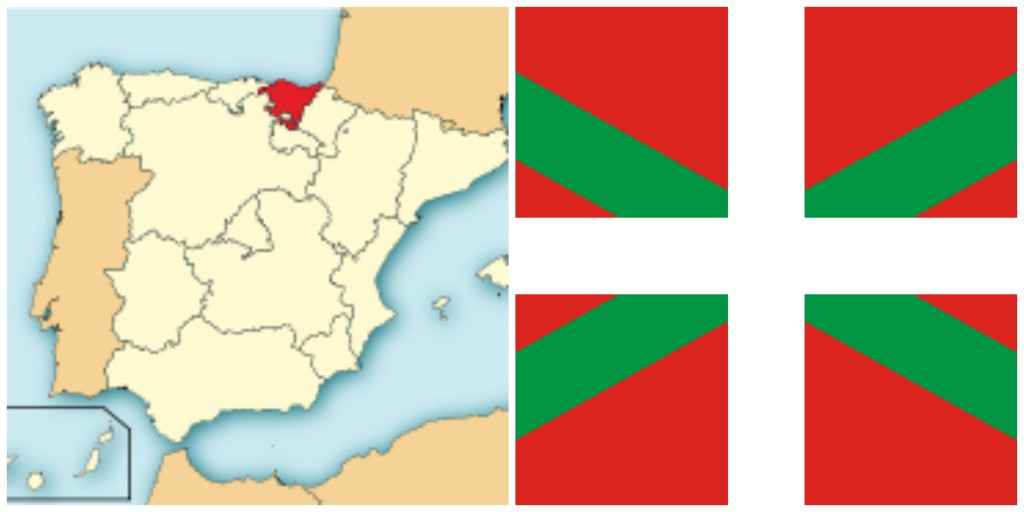

Name: País Vasco in castellano, Euskadi in Basque and Pays Basque in French

Population: 2.17 million

Provinces: Three; Álava in the south, Bizkaia on the Bay of Biscay and Guipúzkoa. There are rather three regional capitals cities: Vitoria-Gasteiz, Bilbao and Donostia, though Vitoria is the legislative powerhouse of the comunidad.

When: 3rd of 17, June 2005

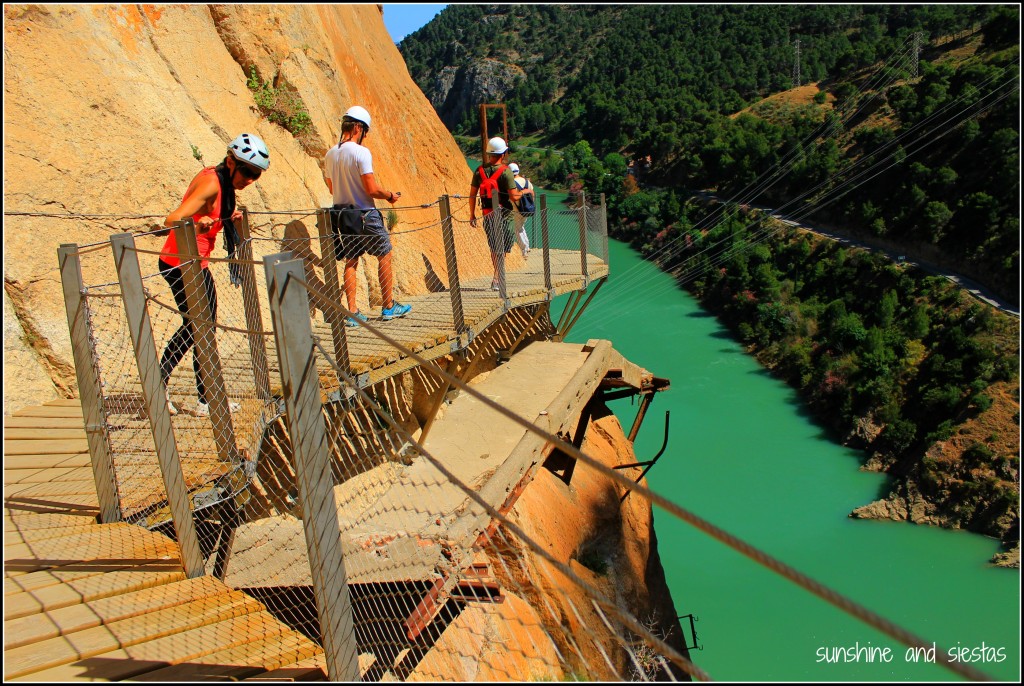

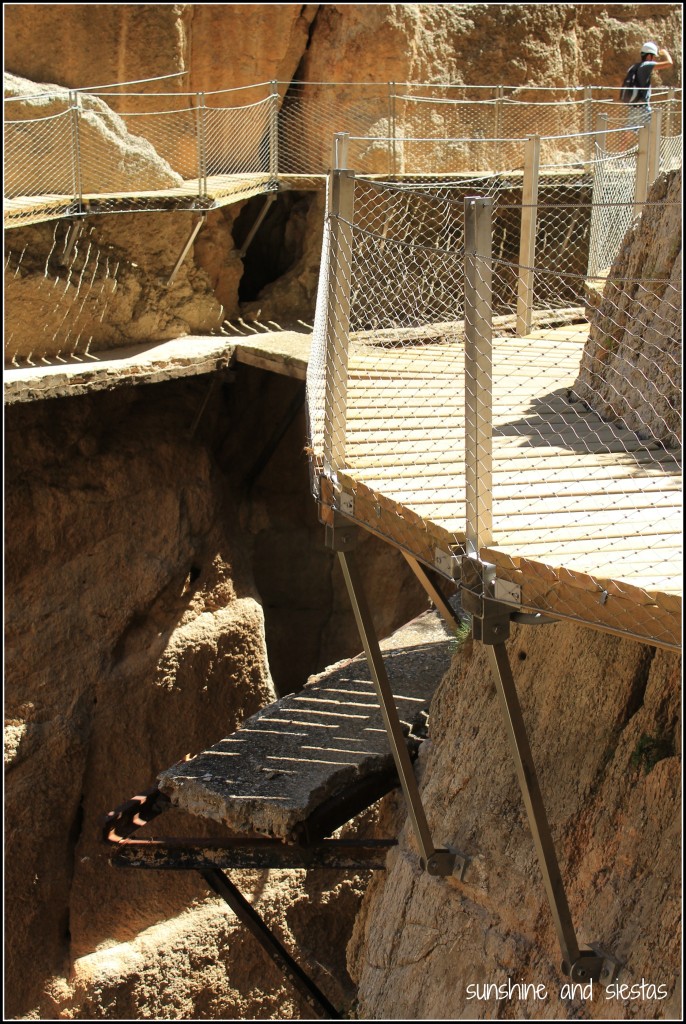

About Euskadi: Located in the Biscay Bay basin and featuring mountains, plains and beach, Euskadi packs a lot of punch for a small region. Quaint fishing villages sidle up to industrial cities, and the mix of sea-mountains-plains make it an attractive pocket of Spain for outdoor enthusiasts.

Anyone who has studied Spanish will know that there are two co-official langauges in Euskadi: Castillian Spanish and Basque. After centuries of repression and intense waves of immigration, the language is making a comeback and cries for independence from Spain are becoming louder.

But I’m ahead of myself.

The Basque people have traits that are untraceable to other ethnic groups, and their language shares no common roots with other European tongues. These indigenous people have long inhabited what is now the Basque region, which makes up the northeast part of Spain and southwest of France (St Jean de Luz and Biarritz are worth day trips!).

Though their exact origin is hotly debated, the Basque are said to come from the Vascon tribes that lived at the foothills of the Pyrenees mountains. For centuries they were left unattacked by the various groups that passed through the Iberian penninsula until finally falling to Castillian forces in the 16th Century.

After years of linguistic and cultural freedom, the constraints put on the vascos from the Spanish crown were surprisingly minimal until the Carlist Wars of the 19th Century, and Franco’s rise to power after the Spanish Civil War meant that euskera was banned and the region lost all of its self-governing rights in an attempt to homogenize Spain.

Two decades later, the Basque Separatist group, Euskadi Ta Astatasuna (ETA) was formed, and over 800 people have been killed in terrorist plots – a friend of my aunt’s father among them. After numerous ceasefires and resurgences, the group announced a definitive end to armed activity in 2011.

In the modern age, Bilbao has drawn the attention of economists for somehow sidestepping the financial crisis, and for a millennia old people, vascos are rather forward-thinking.

Must sees: Euskadi’s three major towns are definite visits: San Sabastián/Donostia’s quaint old quarter boasts more pintxos bars than residents and its Bahía de la Concha is one of Spain’s most photographed beaches (and that’s not to mention the surfing or its world-famous film festival); Bilbao/Bilbo is home to the Guggenheim and a prosperous industrial city; Vitoria-Gasteiz is famous for its parks and gardens and is the administrative capital of the autonomous community.

Further afield lie charming fishing villages and hamlets like Lekeitio or Hondarribia, the jaw-dropping hike to San Juan de Guazalugatxe and Guernika, a city made famous for its role in Nazi bombings and immortalized in a Picasso painting of the same name.

Gastronomy is also a top draw to the region, with four of the top 20 restaurants in the world found here. Pintxos – small, generally seafood-based tapas served atop bread – are the north’s equivalent of tapas. Revelers take part in bar crawls called txikiteo, often imbibing in a sparkling white wine called txacoli or Alavese wines, which form part of the D.O. La Rioja.

Culturally speaking, Basque have their own traditions of Santa Claus, throw enormous parties and have long traditions of Basque strength sports. Local lore pervades daily life and, like Navarra, it’s a place where cultural roots have held firm throughout centuries.

Finally, a note on the weather: it’s not very reliable, particularly in Bilbao and San Sebastián.

My take: There was some truth to my initial observations of Euskadi, but as someone who was clueless about Spanish history and hadn’t even been to Madrid, were largely wrong. I traveled north a few years later with a friend, far more interested in what the region had to offer and more acutely aware of the differences between the Basques and the rest of Spain – and in far more than just language.

Andalucía and País Vasco couldn’t be more different, as evidenced in the hugely popular film Ocho Apellidos Vascos, in which a sevillano de pura cepa falls for a vasca on her bachelorette weekend in Sevilla. Rafa is as sevillano as they get, and follows Amaia up to her small town hidden deep within Euskadi, trying to win her – and her father’s – heart.

The film is a bit over the top, of course, but highlights how regionalism is still a big thing in Spain, and no one embraces it like the vascos. The main cities just feel like they’re not as Spanish as Madrid or Seville or Salamanca. Its citizens have darker features and seem to carry themselves differently. Food is a big deal, as is surfing, Athletic and txacoli from what I’ve gathered.

Suffice to say, I’m keen to travel back to País Vasco as soon as possible.

Have you ever been to País Vasco? What do you like (or not) about it? Check out the blogs Christine in Spain, a Thing With Wor(l)ds and Como Perderse en España for excellent insight into life in the region!

Want more Spain? Andalucía | Aragón | Asturias | Islas Baleares | Islas Canarias | Cantabria | Castilla y León | Castilla-La Mancha | Cataluña | Extremadura | Galicia | La Rioja | Madrid | Murcia | Navarra